I was recently reading L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz and I noticed something funny: Baum really developed a world where anything is possible right from the start of his book. And, he was able to do it in just a few short pages. In this post, we are going to examine worldbuilding with L Frank Baum.

What is worldbuilding?

As it is defined, worldbuilding is exactly what it sounds like—the act of building fictional worlds in literature. The following passage from an article about empathy in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road sums up the importance of creating creating a compelling world:

“A reader’s experience of narrative empathy is closely related to the reception phenomenon of immersion, the phenomenological experience of being transported into a fictional world while in the act of reading” (White).

What this means is that when we talk about worldbuilding with L Frank Baum, we establish the feeling that we are having realistic experiences in a fictional world. Therefore, the world around us is a living, breathing thing. And that thing can be touched and interacted with if only in our minds.

“Empirical evidence confirms that readers respond to written narratives at a bodily level through perceptual simulations triggered by the act of reading” (White).

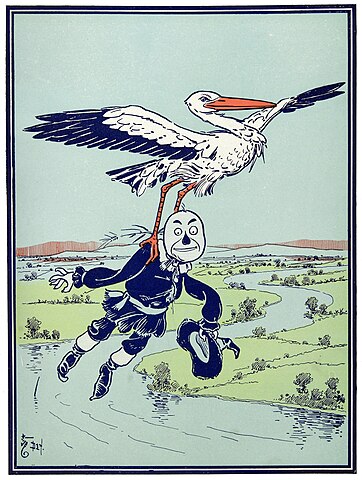

These “perceptual simulations” allow us to see Uncle Henry and Aunt Em in all their dreariness. We can also see the cyclone on the horizon, or the munchkin council aside the good witch in Oz. The reader feels the reality.

This is of course astounding because the term worldbuilding has such a weight in literary circles. There are authors who are synonymous with worldbuilding: Isaac Asimov, George R.R. Martin, Terry Pratchett, and Robert E. Howard (to name a few). Nevertheless, classic children’s literature from Roald Dahl’s BFG to E.B. White’s Stuart Little brings the reader into the world with a skillful efficiency. There is definitely something to learn from their ability to convey worlds. Examining these examples can help you as a writer, whether you are just writing for fun or working on your magnum opus.

Worldbuilding with L Frank Baum

Relating to Characters and the World

It is not just the empathy of the characters we are worried about. It is also the empathy of the world, too. The sense of immersion that readers often gravitate toward are ones that they can relate to through their own reality. This is offered by Baum in The Wizard of Oz. In other words, the reader needs to feel an experience when they read. For a writer, that is not always easy to convey through text.

However, let us look at an example from The Wizard of Oz:

“Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cooking stove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three or four chairs, and the beds” (Baum).

We do not need a full description of the land to tell us about the world in which Dorothy lives. Even if it is extremely close to our own reality. Kansas, during Dorothy’s lifetime, was nearly uninhabited (or at least neighbors were fairly nonexistent). Similarly, Baum’s descriptions tell us about the difficulty of building, living, and finding joy in this place. Though, we do not need eight pages of descriptions of grass and the lack of trees and the gray sky and what Uncle Henry is wearing and how Dorothy looks to understand that fact. All we need is a strong description of the scarcity of Kansas, and suddenly, we are there. We understand the family, the economics, and we could possibly guess why Dorothy’s family ventured out into that sparse country.

Sparsity is Key

Furthermore, when Dorothy arrives in Oz in chapter two, we do not get much of a description of the world. Is this the fault of the author? I do not think so. I believe Baum has bigger fish to fry through the interactions between Dorothy, the munchkins, and the good witch.

“There were lovely patches of green sward all about, with stately trees bearing rich and luscious fruits. Banks of gorgeous flowers were on every hand, and birds with rare and brilliant plumage sang and fluttered in the trees and bushes. A little way off was a small brook, rushing and sparkling along between green banks, and murmuring in a voice very grateful to a little girl who had lived so long on the dry, gray prairies.”

In providing contrast, Baum has realized his world in a way that is both efficient and creative (here is the opposite of what is known to Dorothy). Similarly, he describes the munchkins as “oddly dressed” with “round hats that rose to a small point a foot above their heads, with little bells around the brims that tinkled sweetly as they moved” (Baum). After a short comparison of these munchkins to Uncle Henry and of the witch to Aunt Em, the conversation begins, and Dorothy learns about the death of the Wicked Witch of the East and where she must go to return to Kansas.

Conclusion

When worldbuilding with L Frank Baum, we can see that he expertly builds his world through sparse description and dialogue. That is the one thing we can learn as writers is the following: less is more. What this means is that when you feel as though you need to describe the world and everybody in it, maybe take a moment to consider how using less description (and more concise description) could benefit the reality in your stories.

Works Cited

Baum, L. Frank. “The Wizard of Oz the First Five Novels.” Fall River Press, 2014.

WHITE, CHRISTOPHER T. “EMBODIED READING AND NARRATIVE EMPATHY IN CORMAC MCCARTHY’S ‘THE ROAD.’” Studies in the Novel, vol. 47, no. 4, 2015, pp. 532–549. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26365200. Accessed 14 July 2021.