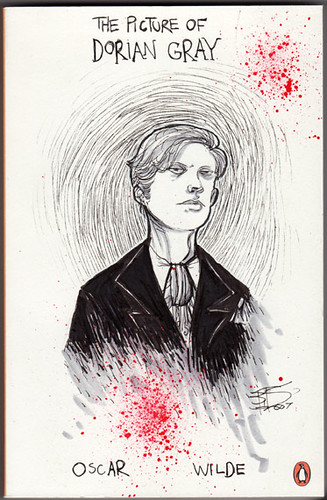

The story of Oscar Wilde is an intriguing one. Much like Thomas Pynchon, there is a lot of mythos surrounding his character and exploits. His literary achievements are notable, and he is also responsible for writing a pivotal piece of Victorian literature, The Picture of Dorian Gray. This novel explores the meaning of art and its reflection against hedonistic values. It’s quite a compelling piece.

The Plot of Dorian Gray

The story tells the tale of Dorian Gray, whose friend, Basil Hallward, painted a picture for and that hangs in Dorian’s home. Due to this fact, Dorian falls in love with his own attractiveness, and wishes that he could stay young forever.

Ostensibly, this wish is granted, and as Gray explores a lifestyle of moral degradation, his portrait becomes more and more disgusting and corrupted. Gray, meanwhile, remains young and beautiful. The conniving, hedonistic Lord Henry Wotton also pushes Gray further into his immoral lifestyle. Others experience Gray’s attitudes more severely, and soon murder and death are on the table. Like a Shakespearean sonnet, Gray’s guilt conflicts with his ambitions.

Over the course of the next 18 years, Gray is “drawn to evil” and finds that the portrait of himself is truly suffering the effects of his own violent and untoward behavior. At the conclusion of the novel, Dorian attempts to do away with the painting, as he is bent on being a better and more moral person, and so he stabs the portrait with a knife. However, by stabbing the portrait, Gray feels the full effects of the blow. His servants find the remains of “a loathsome old man dead on the floor with a knife in his chest and a portrait of a beautiful young man” on the wall (Britannica). On the wall, a portrait of a beautiful, young Dorian Gray stands resolute.

Dorian Gray Background

The novel The Picture of Dorian Gray appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine in 1890. It is a story perfect for the Victorian age due to its attitudes in modesty and artistic exploration. While a novel about aesthetics, it also falls into a few genres, whether that be a cautionary tale, horror story, or historical drama.

“… it is as much a philosophical treatise on morality and the meaning of life as a Gothic horror,” states critic Tony Canavan. “In fact there is little horror in the conventional sense—no rampaging monsters, haunted castles and so on. The action is more psychological, as Dorian, aided by Lord Henry and a ‘little yellow book’, is seduced by the license to do anything” (Canavan).

After publication, it became a controversial book. It challenged the values of contemporary society, which created its scandalous reputation. At the same time, the novel explores Wilde’s values as a writer and artist, and his values has a human being. Immoral action in the novel is a direct critique of those in society that live without consideration to others.

Lasting Impression of Dorian Gray

The idea of “art for art’s sake”–one of Wilde’s approaches to creativity–is alive in this book. The themes it tackles are heady issues, yet the never get muddled in the boredom of excessive description. Wilde once stated that he would use every word in the dictionary if possible when writing a novel if he could, and one gets this from reading his verbose diction. Still, it is artistic in the way Wilde sees art—somehow more open and seemingly reflective of one’s true self, both literally and figuratively.

Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray also discusses morality in a pretty black and white way. Again, the Victorian era’s influence is evident in the novel. The novel informs us of the perils of narcissism and of hedonistic value. As some sources have stated, while Dorian Gray is not one of Wilde’s best books, it is certainly unique due to its earnestness.

“For me, Dorian Gray is special – not necessarily Wilde’s best work but unique in his canon – because it’s so sincere: ineffably, inescapably, absolutely,” he writes. “It’s a very good novel anyway: moving, exciting, full of dread, angst, horror, lucidity… and a great love, I think, for mankind and for the artist’s own self” (McManus).

Works

“The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Britannica. Web.

Canavan, Tony. “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Books Ireland, no. 381, 2018, pp. 26–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26564228. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020.

McManus, Darragh. “Dorian Gray’s true picture of Oscar Wilde.” The Guardian. April 29, 2010. Web.

Discover more from The Writing Post

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.