When I was in middle school, I had the privilege of seeing a collection of popular short stories performed as plays for my entire middle school class. The plays were cleverly sequenced: horror/comedy/horror/comedy. These stories included “The Most Dangerous Game” by Richard Connell, “The Mouse” by Saki, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” by Ambrose Bierce and “The Ransom of Red Chief” by O’Henry. My adolescent brain loved these stories and I remember that event fondly.

Yet, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” made me profoundly sad due to its content. It also impacted my literary tastes immediately, as I grew interested in horror, science fiction, and fantasy. In this post, we will summarize and analyze Ambrose Bierce’s masterpiece “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” because it affected me greatly. And, as for all stories I share, I hope it does the same for you.

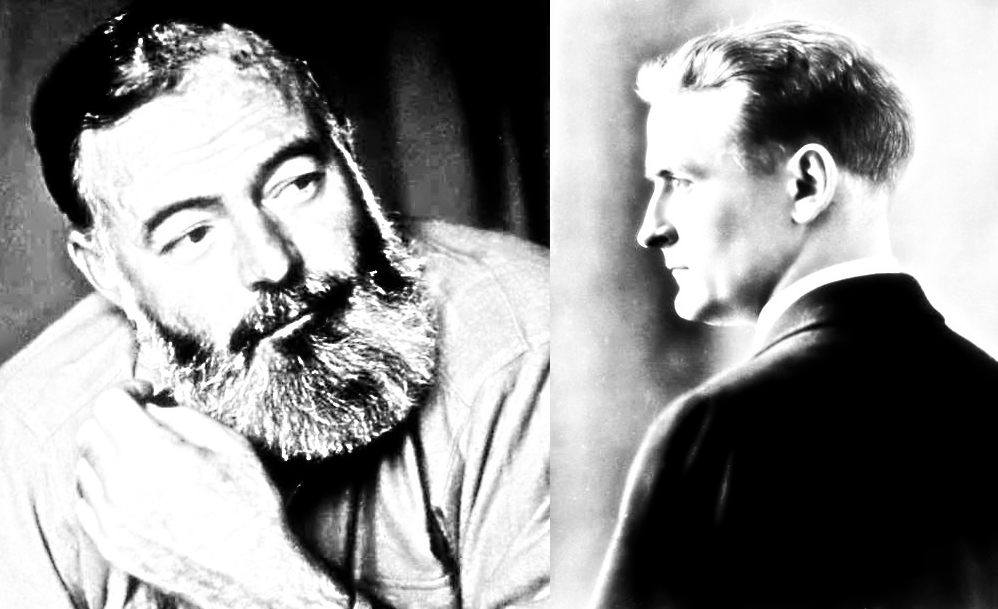

About the Author

Ambrose Bierce, American Author of “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”

Ambrose Bierce was born on June 24th, 1842, in Meigs County, Ohio. During the Civil War, he fought in the battles of Shiloh and Chickamauga in the Indiana infantry unit. Later, he worked at various newspapers as reporter and editor. These papers included the News Letter, the Argonaut, the Wasp, and the San Francisco Examiner. His experience during the Civil War hampered his view of humanity and his stories reflect this vision.

“During his lifetime, Bierce published numerous works. He became well known for his sarcasm and his interest in supernatural topics. Among his most important books are Nuggets and Dust Panned Out in California, Cobwebs From an Empty Skull, The Devil’s Dictionary, and Tales of Soldiers and Civilians.”

Bierce disappeared in Mexico and presumably died in 1914 after joining Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa’s army (Abrams).

Summary

Destroying the Bridge

Set during the Civil War, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is about a Confederate sympathizer, Peyton Farquhar. Farquhar intends to blow up Owl Creek Bridge. He plans to do so because Union soldiers have captured it and intend to use it during the war.

In speaking with a Confederate soldier one evening, Farquhar is told of the particulars:

“’The Yanks are repairing the railroads,’ said the man, ‘and are getting ready for another advance. They have reached Owl Creek bridge, put it in order and built a stockade on the north bank. The commandant has issued an order, which is posted everywhere, declaring that any civilian caught interfering with the railroad, its bridges, tunnels, or trains will be summarily hanged. I saw the order’” (Bierce)

The Confederate soldier, as it turns out, is actually a Union scout passing out bad information. Farquhar is captured and sentenced to death for threat of interfering with the bridge. He is to be hanged at Owl Creek Bridge. However, as he plummets to certain death from above, the rope around his neck snaps and he falls into the waters below. He is able to free his hands, and he swims away to safety amidst rifle and cannon fire.

A Journey Through Fantasy

“As he rose to the surface, gasping for breath, he saw that he had been a long time under water; he was perceptibly farther downstream—nearer to safety. The soldiers had almost finished reloading; the metal ramrods flashed all at once in the sunshine as they were drawn from the barrels, turned in the air, and thrust into their sockets” (Bierce).

From there, Farquhar traverses the North heading South until he is finally back home. He sees his wife in the distance and runs to her. Before they can embrace, he feels “a stunning blow upon the back of (his) neck.” He sees “a blinding white light all about him like the shock of a cannon,” and then it is revealed that he never escaped his moment of expiration; in fact, he has just been executed by hanging at Owl Creek Bridge.

Analysis

Futility

I have discussed futility on this blog before, as it seems to come up in a lot of literature (writers don’t have time for utility). Futility, as I’ve discussed, is a sort of philosophy that acknowledges that—try as we might—we are destined to lose against the fates. With that comes many negative existential questions: why keep living? why do anything? Well, futility addresses many bleak realities that we have to face as humans, which prepares us for the ugliness of truth.

These realities include but are not limited to the following:

- We are not remarkable.

- We will not be remembered.

- We are going to die.

Yes, that’s dour, but it also forces the reader to imagine the real now in their existence and not the fake now they’ve constructed in their head. Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” does the same. It tells us that there is no glory in warfare and violence. Commit violence and you will die. Farquhar was warned of that by the federal scout in disguise, and he still pushed ahead with his plan anyway, expecting to burn the bridge down and save the day (fake now). Unfortunately, that’s not how real life works and consequences happen (real now).

Living With Reality

In the end, we cannot romanticize the fantasies of our life if we are not living in the realities of the now. Bierce’s story veers from present to past to imagined. The realities are shifted, whether standing on a bridge waiting to die, talking to a Federal scout in disguise, or rushing to embrace a wife. Farquhar’s bravery and intent for violence was undone by how he imagined his own bravery and his own fate (freedom), which ultimately killed him no less. Thus, the futility of valor and warfare (and living in a false reality) can be seen in the violence of death and execution.

Farquhar doesn’t drive the enemy away from his home with his actions. He dies. All the while shrouded in the futile illusion of his own honor.

Works Cited

Abrams, Garry. “Stranger Than Fiction : Mystery: The case of Ambrose Bierce, the disappearing author, may have been solved by the publisher of a new collection of the writer’s short stories.” Lost Angeles Times. June 25, 1991. URL: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-06-25-vw-1440-story.html

Bierce, Ambrose. “An Occurence at Owl Creek.” Millennium Fulcrum, 1AD, gutenberg.org/files/375/375-h/375-h.htm.